A Cautionary Tale Explaining the High Cost of Health Care

Having spent decades as a health policy analyst, I know one thing for certain: Everyone has at least one personal story related to health care, either their own or a close relation’s, which often informs their opinions about the system.

In my case, an evolving mini-saga over the last several months confirmed my prior belief: Health care costs too much in part because no one can find out exactly what it costs — and few people have any incentive to do so.

Low-Ball Estimate

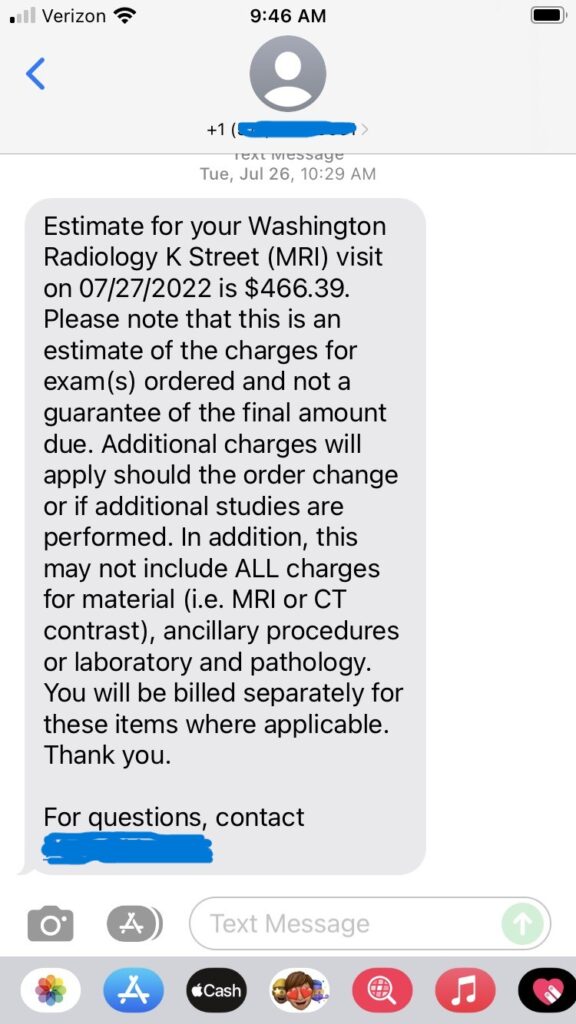

Over the summer, lingering discomfort from an ankle sprain prompted my orthopedic surgeon to suggest an MRI. I went and scheduled the imaging study at Washington Radiology, and the day before my appointment received the below text message:

Having done some research online into the price of ankle MRIs in the Washington area, I found the quoted cost reasonable and decided to go ahead with the procedure.

In late August, I received an Explanation of Benefits from CareFirst Blue Cross, my insurer, followed closely by a bill from Washington Radiology. Neither the amount Washington Radiology billed CareFirst ($1,503) nor the amount of out-of-pocket expense that CareFirst allowed, and which Washington Radiology billed ($518.22), matched the $466.39 estimated cost that Washington Radiology gave me ahead of the MRI. So, given my background in health policy, I decided to investigate why my charges exceeded the original estimate.

Bureaucratic Run-Around

I called Washington Radiology and asked someone to explain the discrepancy between the estimated amount and the charge on my bill. The customer service representative didn’t seem to know where the text I received had come from. She asked me to fax the information to her and pledged to get back to me.

I never heard back from the customer service rep. In early October, I received a follow-up bill from Washington Radiology, again seeking $518.22 from me, whereupon I called to ask about the status of the questions I had raised more than a month previously. This customer service representative told me Washington Radiology had finished its internal investigation over a month ago (how nice of them not to tell me).

This representative also couldn’t tell me where the $466.39 estimate that I received via text message came from. Instead, he suggested I contact CareFirst, my insurer, to inquire with them about my benefits — a suggestion that didn’t make much sense, as Washington Radiology and not CareFirst had sent me the estimate in the first place.

I followed up with several additional inquiries to Washington Radiology via their website, along with a call to the company’s corporate offices. I explained that I planned to write an article about my experiences, and what the discrepancy between the estimated cost and what I was charged said about patients’ ability to act as health care consumers.

Washington Radiology never responded to my online messages or my phone call. However, just after Thanksgiving, I received a new bill that included lines saying, “Per Provider Request — Reduced Rate,” which lowered my bill to the $466.39 amount I was originally quoted in the July estimate. Apparently, months of inquiries prompted Washington Radiology to lower its bill in my case — but not to provide an explanation as to why their charges didn’t sync with the estimate in the first place.

Snippy Customer Service

As for CareFirst, I did call them to ask about their policies regarding estimated costs and whether and under what circumstances the insurer (as opposed to a doctor or other provider) would provide that information to patients. During that conversation, a customer service representative told me that CareFirst “cannot guarantee any estimate we provide.” In response to my assertion that no other service or industry (e.g., auto repair, construction, etc.) will not give customers a guaranteed price in advance, the representative replied, “That’s because we’re insurance.”

I told the agent that her position effectively meant patients could get charged any amount by a doctor and insurer after the fact, notwithstanding any efforts they made to ascertain the costs of a procedure ahead of time. The agent reiterated that CareFirst would provide cost estimates prior to care as a courtesy to customers, which of course means little if those estimates are not guaranteed.

Following this conversation, I emailed CareFirst to ask for an on-the-record comment for my article. Spokeswoman Jen Presswood sent a reply:

CareFirst cost estimates may vary from actual costs as the unique individualization of healthcare care means that insurers do not know specifically which providers will be involved in the service and what exact items and services will be billed. Congress recognized this challenge by creating the Advanced Explanation of Benefits (AEOB) under Section 111 of the No Surprises Act, which CareFirst strongly supports. AEOBs have the promise of giving consumers meaningful, trustworthy, and actionable information to guide their healthcare decisions. CareFirst is actively partnering with the Federal government on AEOB implementation to ensure effective implementation.

Presswood’s response ignores the fact that in my case, the procedure in question was very straightforward. In fact, an ankle MRI or other imaging study is among the most “shoppable” of health care services because 1) the procedure is standardized, 2) quality should not be an issue in most cases, and 3) I had time to select the provider I wished for the service. Yet despite the standardized nature of the procedure, I didn’t receive the same charge following the MRI that I did before it.

Presswood’s reference to Advanced Explanations of Benefits raises two additional concerns. First, federal authorities have yet to fully implement this provision of the law, despite a January 2022 implementation date spelled out in statute.

Second, the Good Faith Estimate regulations that federal authorities have already released only allow individuals to raise grievances where charges are “substantially in excess,” by at least $400, of the original estimate. (Good Faith Estimates apply to doctors, hospitals, and medical providers, whereas Advanced Explanations of Benefits apply to health insurers.) In other words, Washington Radiology could have billed me for nearly double the original $466.39 estimate it quoted me for my ankle MRI, and I would have had little legal recourse to file a complaint.

The Problem with Health Care

This story provides a good microcosm of the dysfunction within our health care system. Because most people have their health costs paid by a third party, patients don’t feel the need to investigate what a service costs. As arrogant as it sounded to me (and it was), the CareFirst representative claiming that — unlike practically every other industry — medical providers cannot stand by their estimates “because we’re insurance” represents the attitude within health care. Few people pay the full cost of their treatments, so why should they care about whether a particular price gets raised after the fact?

Of course, we all end up paying sooner or later through higher health insurance premiums and higher levels of taxation in the case of government-funded programs. But the attitude that providers don’t have any obligation to transparency remains pervasive throughout health care, as my experience showed.

Washington Radiology did lower its bill to the amount of my initial estimate — eventually. But strictly speaking, the $51.83 I “saved” probably didn’t make up for the months of emails and phone calls necessary to get that adjustment. And from Washington Radiology’s perspective, that’s probably the point; if they can charge more than their initial estimate, and 90-95 percent of patients don’t bother to complain, and/or give up when Washington Radiology gives them the proverbial run-around, then those higher charges go straight to their bottom line.

It shouldn’t take an act of Congress to get providers of a service to give customers an estimate of charges in advance of a medical procedure, and it shouldn’t take months of pestering to get a medical provider to honor that original estimate. If we had more people using their own money to pay for health care goods and services, perhaps patients could finally demand and receive a more transparent, and rational, health care system.

This post was originally published at The Federalist.