How AARP Puts Profits over Principles–And Patients

A PDF version of this report is available on the American Commitment website…

Some Americans might think of AARP, formerly known as the American Association of Retired Persons, as a membership and advocacy organization. However, the reality has proven far different. AARP has grown into a marketing and sales firm with a public policy advocacy group on the side. And AARP’s prime source of tax-free revenue from that marketing operation comes from its relationship with UnitedHealthGroup, the nation’s largest health insurer.

For decades, AARP has been accused of questionable business practices from numerous quarters: Federal officials, who suggested a business arrangement AARP proposed (but never implemented) could violate federal criminal statutes, the editorial board of the New York Times, and former AARP employees themselves.[1] The organization’s business practices effectively overcharge seniors who purchase insurance coverage from the organization—including Medicare supplemental policies, called Medigap insurance—to fund its own operations. AARP’s revenue from these sales, and from UnitedHealth, which licenses AARP-branded Medigap and Medicare Advantage coverage, has grown year after year. In the nine years since Obamacare’s enactment in 2010, the organization has received nearly $5 billion tax-free in revenue from UnitedHealth.

As it rakes in billions of tax-free dollars in UnitedHealth cash, AARP has abandoned the seniors and vulnerable patients who have placed their trust in the organization. While AARP claims that Obamacare ended “discrimination” against individuals with pre-existing conditions, the organization somehow forgot to ensure that the law’s package of insurance changes—including a ban on denying coverage to individuals with pre-existing conditions—applied to its lucrative Medigap policies.[2] As a result, some seniors and AARP members with pre-existing conditions often cannot obtain access to AARP-branded Medigap policies, because the organization has put protecting its prime source of revenue over the principles to which it purportedly adheres.

An exploration of the record shows not just that AARP holds serious conflicts of interest, but that AARP’s financial conflicts have prompted the organization to abandon its principles on numerous occasions, pursuing financial gain for itself and its partners over the organization’s stated objectives—and its members. Congress should follow up on these facts, and its own prior investigations, by further exploring the unholy alliance between AARP and UnitedHealthGroup.

A Profitable “Non-Profit”

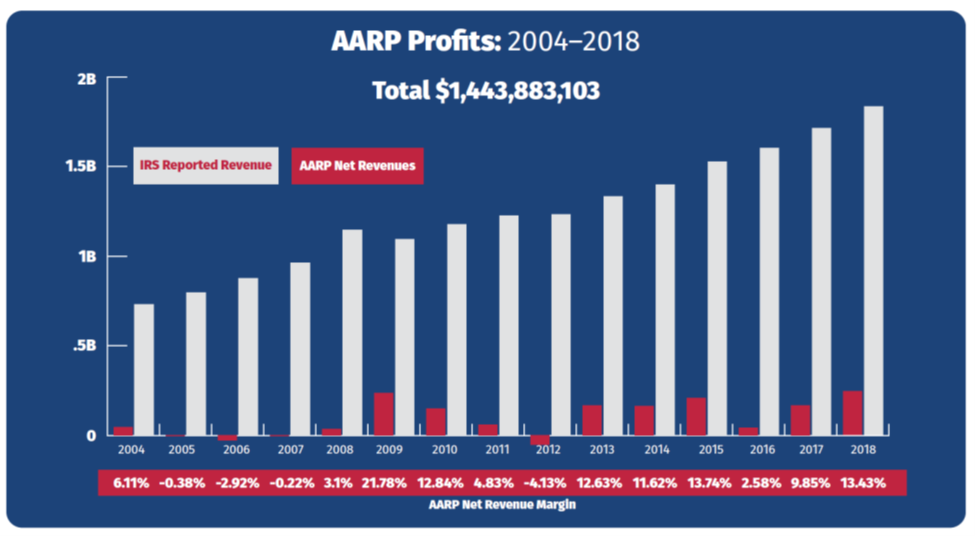

Despite the organization’s status as a non-profit tax-exempt entity organized under Section 501(c)(4) of the Internal Revenue Code, AARP has found its business very enriching indeed. According to its 2018 Form 990 filed with the Internal Revenue Service, the organization reported net income—that is, revenues in excess of expenses—of $246,463,998.[3] That surplus of nearly a quarter-billion dollars represents a net margin equal to more than 13.4% of AARP’s total revenues.[4]

Moreover, 2018 does not represent an anomaly when it comes to AARP’s fortunes. After hiring Barry Rand as CEO in early 2009, AARP converted a string of modest annual results into a series of large financial gains. Under Rand and Jo Ann Jenkins, who succeeded him in 2014, AARP has achieved a total of nearly $1.4 billion in net profits since 2009, achieving financial gains in nine out of those 10 years.[5] Moreover, its net revenue margin has averaged nearly 10%, far more than the average profit margin of some industries.[6] For instance, of seven major health insurers listed in the Fortune 500, none had a 2018 profit margin exceeding 5.42%.[7]

A Marketing Behemoth

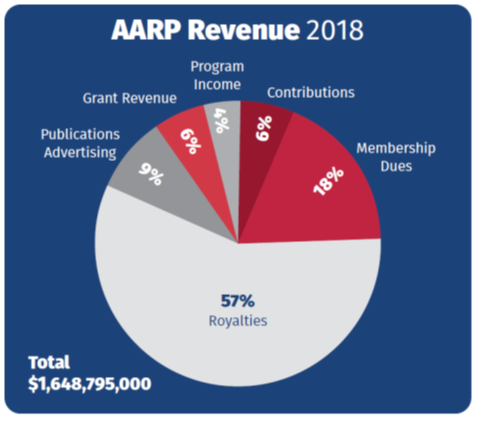

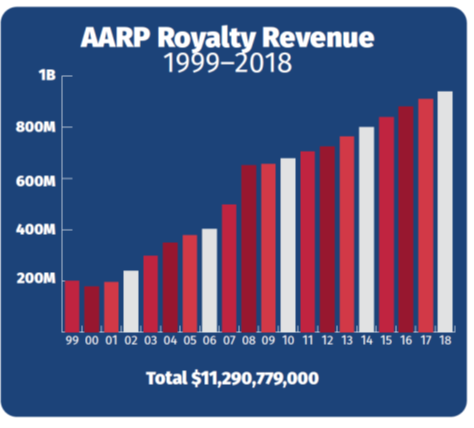

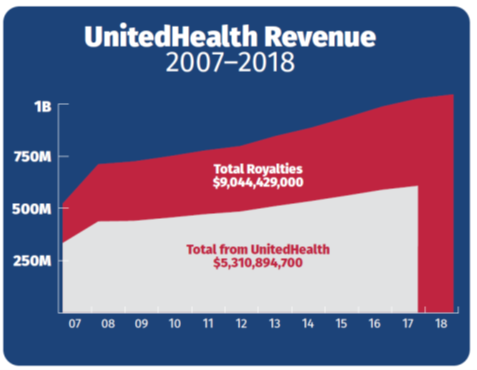

For all the revenue AARP receives from membership dues—approximately$300 million in 2018, according to its most recent consolidated financial statements—the organization receives more than three times that amount selling AARP-branded goods and services to its members.[8] In fact, the organization’s “royalty fees”—which the organization claims constitute payments for the use of its logo, brand, and intellectual property—represent well over half (56.9%) of AARP’s total annual revenues.[9] In 2018, AARP received nearly $1 billion in such revenue from what more appropriately constitutes the sale and marketing of products to members, equal to nearly double the revenues generated by membership dues, grant revenue, and contributions combined.[10]

While other organizations’ revenues fluctuate from year to year, the revenue AARP has generated from selling products to its members has increased every single year for 18 years straight. Since 2000, the company’s business proceeds have increased more than fivefold, from $178.3 million in 2000 to $938.9 million in 2018.[11] In total, over the past 20 years, AARP has made $11.3 billion selling products to its members.[12]

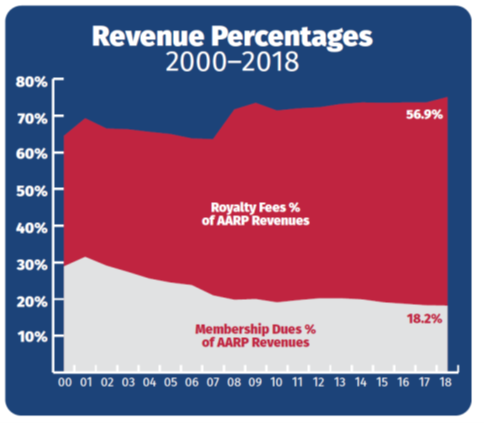

As AARP has expanded its marketing empire, fees from membership dues have grown at a much slower pace. While dues collections have risen over the past two decades, from $141.1 million in 1999 to $299.9 million in 2018, over the past five years (2014-2018) they have remained largely flat.[13] In some years, revenue from membership dues has declined year-on-year—a contrast to the organization’s marketing arm, where revenues have increased every single year since 2001.[14]

The result of the two trends—membership dues growing slowly, and royalty fees growing exponentially—has made AARP much more reliant on marketing income as a share of its overall revenues. Since 2000, membership dues have nearly halved as a percentage of AARP’s total operating revenues, from 28.9% to 18.2% in 2018.[15] Meanwhile, marketing income has grown from 35.6% of operating revenues to 56.9%.[16]

Health Insurance Business Dominates

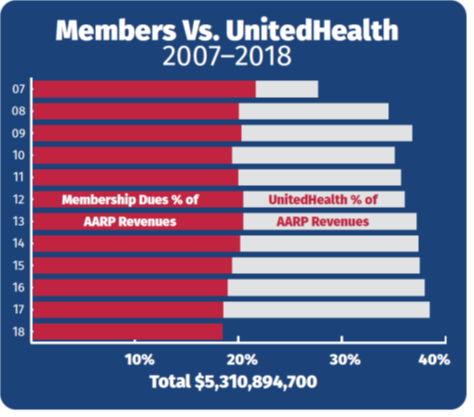

As AARP’s sales and marketing revenue has skyrocketed overall, the percentage of that revenue coming from UnitedHealthGroup has also grown. In 2007, revenue from UnitedHealth represented 57% of AARP’s marketing income, or $283.7 million.[17] By 2017, both numbers had grown substantially: Income from UnitedHealth comprised 69% of AARP’s marketing revenue, and had risen to a whopping $627.2 million—more than double the amount of just a decade previously.[18]

As income from UnitedHealthGroup has grown over the past decade, so too has UnitedHealth’s share of AARP’s operating revenues. As of 2017, income from the sale of insurance products through UnitedHealth exceeded income from membership dues by almost twofold.[19] While member dues comprised only 18.3% of the organization’s total revenue in 2017, UnitedHealth revenue constituted 38.2% of AARP’s operating income.[20]

AARP’s relationship with UnitedHealthGroup, discussed in further detail below, has drawn public scrutiny from Congress and other policymakers. From 2008 through 2017, AARP’s consolidated financial statements disclosed the percentage of marketing revenue coming from UnitedHealth. One could therefore easily calculate the exact amount of revenue AARP received from UnitedHealth, by multiplying total marketing revenues by the percentage of those revenues coming from UnitedHealthGroup.

In total, AARP received more than $5.3 billion tax free from UnitedHealthGroup from 2007 through 2017.[21] Between the year of Obamacare’s passage and 2017, the organization made nearly $4.2 billion in those eight short years.[22]

However, AARP’s 2018 consolidated financial statements failed to disclose the percentage of its marketing revenue that came from UnitedHealthGroup.[23] Therefore, one can no longer calculate the exact amount of income AARP receives from UnitedHealth. We do know that AARP’s marketing revenue has grown every year for the past 18 years (including 2018), and that the percentage of overall marketing revenue coming from UnitedHealth stayed the same or increased every year from 2007 to 2017.[24]

Because AARP decided not to disclose the percentage of 2018 “royalty” revenue received from UnitedHealthGroup to its members or the public—quite possibly due to public scrutiny over its relationship with UnitedHealth—we cannot calculate the amount precisely.[25] However, AARP added a section to its 2018 financial statements regarding revenue recognition, which includes an additional discussion of royalties.[26] Because information in the 2018 Statements includes data for the prior year period, and because AARP did provide information on its revenue from UnitedHealth in its 2017 Statements, we can create a rough approximation of its UnitedHealth revenue in 2018.

In its 2018 financial statements, AARP claimed that $649.2 million of royalty revenue in 2017 came from “health products and services.”[27] In its 2017 statements, AARP noted that a total of $627.2 million in royalty revenue—or 96.6% of the “health products and services” royalties—came from UnitedHealth.[28] If UnitedHealth accounted for a similar 96.6% share of the $680.3 million in “health products and services” revenue in 2018, that would mean AARP received a total of about $657.2 million in revenue from UnitedHealth in 2018.[29]

While this $657.2 million number serves as a mere approximation, it does so only because AARP decided not to disclose to the public exactly how much money it received from UnitedHealthGroup in 2018. However, revenue in this ballpark would mean AARP received nearly $5 billion in “royalty” income from UnitedHealth since 2010, the year of Obamacare’s enactment.[30]

Making Money on Seniors’ Money

AARP not only makes money from UnitedHealthGroup—and its members—directly, it does so indirectly as well. The organization has established a grantor trust, through which it funnels payments for insurance policies issued by UnitedHealth and other insurers, including MetLife, Genworth, and Aetna. As its financial statements explain:

The [AARP Insurance] Plan, a grantor trust, holds group policies, and maintains depository accounts to initially collect insurance premiums received from participating members. In accordance with the agreements referred to above, collections are remitted to third-party insurance carriers within contractually specified periods of time, net of the contractual royalty payments that are due to AARP, Inc., which are reported as royalties in the accompanying consolidated statements of activities.[31]

In plain English, this language means that members pay premiums—including the “royalty fee” UnitedHealth pays to AARP—via the trust, and the AARP trust then pays the premium to UnitedHealth, after taking out its own “royalty fees.”

But in the process, AARP invests the funds from the day they receive the payments from seniors until the “contractually specified” time during which they transfer the payments to UnitedHealthGroup and other insurers. Investing seniors’ premium payments for a short period might seem insignificant. However, given the massive sums involved—the grantor trust processed a total of $11.4 billion in payments from AARP members in 2018—the investment gains quickly add up.[32]

Over the past two decades, AARP has made more than half a billion dollars—$564.9 million, to be exact—investing seniors’ premium payments via its grantor trust.[33] In only three years—during the market crash in 2008, in 2015, and again in 2018—did AARP lose money in its investments made via the grantor trust.[34] On average, however, the organization made $30.3 million per year via these investments—much, but not all, of which came from premium payments made by members for UnitedHealthGroup insurance.[35]

Extravagant Compensation & Benefits

In 2018, AARP paid its CEO, Jo Ann Jenkins, a total of $1,341,675 in salary, benefits, and other compensation.[36] The payout continued a long-standing tradition of the organization spending large sums on executive compensation. In 2006, AARP paid its then-CEO, Bill Novelli, over $2 million in compensation—this in a year when AARP suffered a nearly $26 million shortfall.[37] And when Novelli’s successor, Barry Rand, retired on September 1, 2014, he received nearly $1.7 million in compensation—after working for only eight months out of the year.[38]

But the high compensation levels do not stop with AARP’s CEO. Of a total of 13 AARP employees—officers, key employees, and other highly compensated staff—listed on the organization’s 2018 Form 990 filed with the Internal Revenue Service, all received more than $450,000 in total compensation.[39] These figures only include the salaries and compensation for key executives for which the IRS requires disclosure. By definition, it does not include other AARP executives, or executives of the AARP Foundation, a separate legal entity with its own salaried officers and staff.

In fact, AARP pays most of its employees far more than the average senior receives in income and/or Social Security benefits. According to its IRS filing, in 2018 more than half (1,128) of AARP’s total employees (2,015) received reportable compensation from the organization in excess of $100,000.[40] Dividing the organization’s total spending on employee compensation in 2018 ($347,536,725) by its number of employees (2,015) reveals that AARP employees received an average of $172,484.80 in salaries, benefits and other compensation.[41]

By comparison, in 2018 the average senior citizen received $1,404 in monthly Social Security benefits.[42] That $16,848 total annual benefit represents less than one-tenth the total compensation provided to the average AARP employee. To put it another way, in 2018 AARP paid $47 million more in compensation to its employees than the organization itself received in dues from its members—and over $220 million more than AARP spent giving grants to other organizations.[43]

Furthermore, AARP officials have admitted that the organization’s overall revenue totals—including “royalty fees” obtained by selling seniors AARP-branded products— impact the compensation decisions of its senior executives. As one anonymous staffer told the Washington Post, “Revenues are very important. You have to make your numbers.”[44] In other words, if AARP does not receive enough “royalty fees” from selling products to its members, its CEO and other senior executives could lose bonuses or other financial compensation.

Medigap: The AARP Cash Cow

As noted above, AARP has received a stunning amount of revenue—nearly $5 billion—from UnitedHealthGroup over the past decade. However, the organization does not delineate how much of said revenue comes from each of the three types of plans UnitedHealth sells: Medicare Advantage plans, Medicare Part D prescription drug coverage, and Medigap supplemental coverage. A 2011 report by the House Ways and Means Committee found that AARP brands hold dominant market shares in all three categories.[45]

However, among the three forms of coverage, AARP receives a flat annual “royalty fee” from UnitedHealth covering the sale of its AARP-branded Part D and Medicare Advantage plans, regardless of the plans’ enrollment. Conversely, for Medigap coverage, AARP receives a “royalty fee” from UnitedHealth equal to 4.95% of premium revenues paid.[46]

This percentage-based “royalty fee” gives AARP a strong financial incentive to aggressively market, sell and renew as many Medigap policies as possible—and the most expensive policies at that—because AARP receives nearly five cents for every additional premium dollar its members pay to UnitedHealth. Perhaps as a result, some of AARP’s own members have considered these revenues not so much “royalty fees” as “kickbacks.”[47]

That 4.95% “royalty fee” represents a sizable share of premium dollars paid. To put the figure into perspective, it exceeds the 2018 profit margins of five major health insurers (Anthem, Centene, Humana, WellCare, and Molina), and approaches the profit margins of the other two (UnitedHealthGroup and Cigna).[48]

More to the point, AARP’s “royalty” margins come even though the organization bears no financial risk. The organization often notes that it is “not an insurance company”—a very true statement.[49] Insurers like UnitedHealth, Anthem, and Humana must take on financial risk, and can lose money in down markets or under turbulent circumstances. For instance, insurers lost an estimated $2.7 billion selling individual insurance policies in 2014, the first year of Obamacare’s Exchanges, and even more in the year following.[50] By contrast, however, AARP bears no risk, such that it cannot lose—all it has to do is sign up individuals and watch the cash roll in by the billions.

To give some sense of the questionable propriety of AARP’s current arrangements with UnitedHealth, in 1997 the group abruptly abandoned its plans for a percentage-based “royalty fee” for selling Medicare managed care plans (the precursor to Medicare Advantage).[51] At the time, government officials believed the arrangement potentially violated the Anti-Kickback Statute, which imposes criminal penalties for anyone who gives a “thing of value” in exchange for referrals of individuals to federal health programs.[52] The then-head of the agency that runs Medicare, Bruce Vladeck, also reportedly thought the arrangement could cause AARP to “lose its credibility as an advocate for its members if it endorses HMOs [Health Maintenance Organizations] and receives a financial reward.”[53]

Even though potential concerns that the arrangement violated a criminal status led AARP to abandon its plans for percentage-based “royalties” to sell Medicare Advantage coverage, the organization has retained that approach when selling Medigap coverage—and has profited handsomely from it. Publicly available information suggests that most of AARP’s revenue from UnitedHealth comes via the sale of Medigap plans.

According to UnitedHealth’s annual filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission, in 2018 the insurer enrolled 4,545,000 individuals in Medicare supplemental (i.e., Medigap) plans.[54] Multiple surveys suggest that the average Medigap policy costs seniors approximately $150 per month, or around $1,800 per year.[55] Based on an average Medigap premium of $1,800 annually, UnitedHealth received about $7-8 billion in total Medigap premiums from its members in 2018. AARP’s 4.95% share of that sum would total roughly $350-400 million.[56]

Again, these numbers represent approximations, because AARP does not disclose the amount of money it receives from selling various health insurance policies—and in its 2018 financial statements, decided not to disclose the exact sum it receives from UnitedHealth at all. But it strongly suggests that the majority of the more than $600 million it receives from UnitedHealth in “royalty fees” comes from the sale of Medigap plans. It also suggests that AARP made far more money in 2018 selling Medigap insurance to its members than the $300 million it received in membership dues.[57]

Financial Conflicts—And Secret Lobbying Campaigns

The percentage-based “royalty” formula gives AARP strong financial incentives to maximize enrollment in Medigap coverage. Whereas an additional participant in AARP-branded Part D plans or Medicare Advantage coverage provides no financial benefit to the organization, AARP’s bottom line benefits with every new person it can get to sign up for Medigap coverage. Likewise, AARP also benefits financially when it can entice individuals to sign up for more expensive Medigap policies, because it receives a percentage of every additional premium dollar seniors pay.

Even a former AARP chief executive has admitted that the organization faces financial conflicts regarding its insurance ties. In 2012, Bill Novelli, AARP’s CEO from 2001 through 2009, said that “it’s fair to say that AARP does have a financial interest in Medigap insurance because it’s a significant revenue raiser for them. If Medigap were somehow reduced, then AARP would have a financial reduction.”[58]

That financial conflict played out in 2011, when AARP secretly lobbied against changes to Medigap insurance—without disclosing its financial conflicts to Congress. At the time, lawmakers were considering changes to Medigap insurance that would have created a catastrophic cap on expenses in traditional Medicare, while requiring seniors purchasing Medigap coverage to pay deductibles and co-payments.[59] In total, these changes would have lowered Medigap premiums so dramatically that most seniors would have saved significant sums, even after paying the new co-payments out-of-pocket. A Kaiser Family Foundation analysis concluded that nearly four in five seniors (79%) would benefit financially, to the tune of an average savings of $415 per year.[60]

But if seniors win, saving money by paying smaller premiums, AARP loses—to be exact, it loses 4.95 cents out of every dollar seniors save by paying lower Medigap premiums. Perhaps unsurprisingly, then-CEO Barry Rand wrote to a congressional “supercommittee” established to suggest changes to entitlement programs in October 2011, stating that AARP opposed any changes to Medicare or Medigap.[61] But in setting out AARP’s position on Medigap reform, Rand “did not mention AARP’s dominant role in the Medigap market,” or for that matter the organization’s financial incentive—to say nothing of the financial incentives associated with Rand’s own compensation—to keep Medigap premiums high and maximize AARP’s “royalties.”[62]

Another former AARP executive, Marilyn Moon, admitted that the organization had “an inherent conflict of interest,” because AARP “ended up becoming very dependent on sources of income.”[63] With respect to the stealthy way AARP tried to thwart Medigap reform, Moon noted:

Any way you look at changes in Medigap that people are talking about, I think it’s good for beneficiaries, and anybody who is opposing that who claims they are looking out for beneficiaries, you have to wonder why.[64]

Of course, in the case of AARP, one doesn’t have to wonder: The financial conflicts are obvious to everyone who understands how its “royalty fee” arrangements operate.

Discriminating Against the Most Vulnerable

The congressional supercommittee did not represent the first time in which AARP’s business practices took precedence over the principles to which the organization purportedly adheres. In 2009 and 2010, AARP failed to follow the health “reform” agenda exemplified by Obamacare. Both AARP and other supporters of Obamacare claim that the law ended “discrimination” against individuals with pre-existing conditions—but that claim does not comport with reality. As it happens, Obamacare exempted Medigap supplemental coverage—the type of insurance from which AARP derives much of its revenue—from the law’s new regime regarding pre-existing conditions.

Under current law, individuals can apply for Medigap coverage on a guaranteed issue basis—that is, without insurers considering their pre-existing conditions—only in the six months after their 65th birthday.[65] As a result, seniors who originally enroll in Medicare Advantage programs when they turn 65, and then switch back to traditional Medicare years later, can have their pre-existing conditions considered if and when they apply for Medigap supplemental coverage.

Another group of vulnerable individuals has little to no access to Medigap coverage at all: Individuals with disabilities. Beneficiaries who qualify for Medicare because they receive Social Security disability benefits cannot apply for Medigap coverage on a guaranteed issue basis until they turn 65. As a result, many of the 8.8 million beneficiaries receiving Medicare coverage due to a disability cannot purchase Medigap coverage, because these individuals by definition have pre-existing conditions.[66]

At the time of Obamacare’s passage, AARP claimed that it wanted to end “discrimination” against individuals with pre-existing conditions. But what did AARP do to ensure that that policy applied to its lucrative Medigap insurance plans? Precious little. Press reports indicate that the seniors’ organization compelled then-Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-NV) to close the “doughnut hole” in the Medicare Part D prescription drug benefit before it would endorse the final version of the legislation.[67] By contrast, AARP imposed no such requirement on Democrats to ensure that Obamacare’s insurance provisions regarding pre-existing conditions applied to the Medigap insurance AARP sells. In fact, it stood idly by while Democrats stripped language applying pre-existing condition provisions to Medigap from the final version of the bill.

An early version of what became Obamacare included language applying the pre-existing condition provisions to Medigap coverage.[68] Later articles, citing anonymous congressional staffers, claimed that lawmakers removed the relevant language prior to the law’s enactment over cost concerns.[69] In June 2009, the Congressional Budget Office concluded that extending pre-existing condition provisions to Medigap coverage would increase the deficit by $4.1 billion over ten years, likely by increasing overall Medicare spending.[70]

But during the debate on Obamacare, AARP claimed vociferously that it “would gladly forego every dime of revenue to fix the health care system.”[71] And at the time of Obamacare’s enactment, AARP generated more than enough annual revenue from UnitedHealthGroup—$411.2 million in 2009, and $427 million in 2010, numbers that have only grown every year since—to pay for the cost of applying the pre-existing condition provisions to Medigap coverage.[72] But rather than trying to apply one of its major goals for Obamacare to the Medigap coverage seniors purchase, AARP chose to protect its lucrative profits instead. The organization eventually endorsed applying Obamacare’s pre-existing condition provisions to Medigap coverage—but only after the law passed, and only after a column in the Wall Street Journal publicly exposed the organization’s hypocrisy.[73]

As for AARP members, a 2011 Washington Post article outlined the implications of the organization’s selfishness, as individuals with disabilities still cannot obtain access to coverage because of their pre-existing conditions. The newspaper profiled Joe Hobson, then aged 63, who ended up on Medicare when a rare genetic condition caused him to lose his sight.[74] He could not obtain affordable supplemental coverage under Medigap, to provide a cap on out-of-pocket expenses that traditional Medicare lacks, because of his disability—and because, in 2009, AARP put protecting its profits over extending pre-existing condition provisions to its prime source of revenue.

Backroom Deals Surrounding Obamacare Greatly Benefit AARP

Obamacare did not just exempt AARP’s lucrative Medigap insurance coverage from its provisions regarding pre-existing conditions. In fact, Medigap insurance received a host of exemptions in the law, and more from the Obama Administration:

- The tax on health insurance companies explicitly exempted “Medicare supplemental insurance policies” from the Obamacare levy.[75] As a result, UnitedHealthGroup, and by extension AARP, did not have to pay their share of the more than $14 billion tax on the Medigap policies they sell.[76] This exemption applied to AARP even though the organization’s revenue from selling UnitedHealthGroup insurance policies exceeds its revenue from membership dues, grant revenues, and private contributions combined.[77] While Congress repealed this tax outright in December 2019, AARP benefited from the Medigap carve-out while the tax was in effect.[78]

- The medical loss ratio standards, which require insurers to pay out 80-85 cents of every premium dollar in benefits, likewise do not apply to Medigap.[79] Instead, Medigap policies are subject to a much lower 65 percent medical loss ratio standard.[80] Had lawmakers applied the stricter 80-85% standard to Medigap, AARP might have lost the ability to skim 4.95% of premium revenues as a “royalty fee.” Instead, however, AARP can continue to receive its massive profits at the expense of its senior citizen members.

- The Obama Administration went even further, exempting Medigap insurance from the rate review process entirely.[81] Obama officials used an interesting logic in justifying this exemption, claiming that Medigap plans “do not appear to be a principle focus of” the law.[82] In other words, because Democrats decided to exempt Medigap from some of the law’s requirements, the Obama Administration decided to exempt it from rate review as well. As a result, to the extent that AARP’s 4.95% “royalty fee” results in higher premiums for seniors, AARP and UnitedHealthGroup do not have to justify those higher premiums through a rate review process.

Just as lawmakers received their own “backroom deals” as part of Obamacare—the infamous Cornhusker Kickback, Gator Aid, Louisiana Purchase, and other legislative earmarks—so too did AARP’s important Medigap business benefit from the special exemptions it obtained from the Obama Administration and a Democratic Congress.[83]

A Compromised Organization

The sordid history of AARP’s dealings in Washington—the backroom deals its lucrative Medigap coverage received in Obamacare, the way in which AARP “forgot” to lobby for pre-existing condition changes in Medigap as part of Obamacare, and the secretive way in which AARP lobbied to kill Medigap reform without informing lawmakers of its financial conflicts—demonstrate how its revenue sources have compromised the integrity of its policy positions.

As one observer noted during the Obamacare debate: “Either you’re a voice for the elderly or you’re an insurance company—choose one.”[84] Sadly, AARP has largely chosen the latter course of action, even as it tries to portray itself as the former.

Congress has already investigated AARP and its financial dealings on more than one occasion. It should do so again, and determine whether any legislative and/or regulatory actions—requiring AARP to disclose its financial conflicts to seniors when they apply for Medigap coverage, for instance—can protect AARP’s members from the organization’s unholy alliance with UnitedHealthGroup.

This report was originally published by American Commitment, and was corrected subsequent to publication to fix a math error regarding investment returns from the AARP grantor trust.

[1] Milt Freudenheim, “AARP Dropping Plans for Royalties in a Health Program,” New York Times April 19, 1997, https://www.nytimes.com/1997/04/19/business/aarp-dropping-plans-for-royalties-in-a-health-program.html; “Can You Trust the AARP?” New York Times May 20, 1996, https://www.nytimes.com/1996/05/20/opinion/can-you-trust-the-aarp.html; Jerry Markon, “AARP Lobbies Against Medicare Changes That Could Hurt Its Bottom Line,” Washington Post December 4, 2012, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/aarp-lobbies-against-medicare-changes-that-could-hurt-its-bottom-line/2012/12/03/aa3e509e-3a8c-11e2-b01f-5f55b193f58f_print.html.

[2] Lynda Flowers and Claire Noel-Miller, “The Ban on Pre-Existing Condition Exclusions Helps Older Americans,” AARP Blog December 28, 2016, https://blog.aarp.org/thinking-policy/the-ban-on-pre-existing-condition-exclusions-helps-older-adults.

[3] AARP Inc., 2018 Form 990, https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/about_aarp/annual_reports/2019/2018-aarp-form-990-public-disclosure.pdf, p. 1.

[4] Ibid.

[5] AARP Inc., Forms 990, 2009 through 2018. While only the 2016, 2017, and 2018 statements are visible on the organization’s website, https://www.aarp.org/about-aarp/company/annual-reports/, all copies of the AARP Forms 990 are available through a ProPublica database, https://projects.propublica.org/nonprofits/organizations/951985500.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Fortune 500, 2019, https://fortune.com/fortune500/2019/search/?industry=Health%20Care%3A%20Insurance%20and%20Managed%20Care. Health insurers include UnitedHealthGroup, Anthem, Centene, Humana, Cigna, WellCare, and Molina Healthcare. The other Fortune 500 company listed under “Insurance and Managed Care,” Magellan Health, focuses on managing behavioral health issues, as opposed to selling health insurance products to individuals and/or employers.

[8] AARP Inc., 2018 Consolidated Financial Statements, March 20, 2019, https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/about_aarp/annual_reports/2019/2018-audited-financial-statement-aarp.pdf, p. 4.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] AARP Inc., Consolidated Financial Statements, 2000 through 2018. While only the 2016, 2017, and 2018 statements are visible on the organization’s website, https://www.aarp.org/about-aarp/company/annual-reports/, Internet searches for “AARP Consolidated Financial Statements” and the year in question reveal that prior years’ statements remain online (albeit not linked from the AARP homepage). Links to specific years’ statements are provided in citations below.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] AARP Inc., 2008 Consolidated Financial Statements, March 30, 2009, https://assets.aarp.org/www.aarp.org_/TopicAreas/annual_reports/assets/AARPConsolidatedFinancialStatements.pdf, pp. 4, 9. The 2008 financial statements represent the first instance in which AARP disclosed the percentage of total royalties coming from UnitedHealthGroup. However, the 2008 statements also included data for the prior year period, making calculations for 2007 possible.

[18] AARP Inc., 2017 Consolidated Financial Statements, March 16, 2018, https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/about_aarp/about_us/2018/aarp-2017-audited-financial-statement.pdf, pp. 4, 11.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid.

[21] 2008 through 2017 Consolidated Financial Statements.

[22] Ibid.

[23] 2018 Consolidated Financial Statements. The relevant language previously appeared in the royalties section of the statements’ Summary of Significant Accounting Practices. The 2018 statements’ Summary of Significant Accounting Practices eliminates the discussion of royalties entirely. Compare pp. 8-13 of the 2017 Statements with pp. 8-13 of the 2018 Statements.

[24] 2008 through 2017 Consolidated Financial Statements.

[25] Chris Jacobs, “How AARP Made Billions Denying Care to People with Pre-Existing Conditions,” The Federalist October 11, 2018, https://thefederalist.com/2018/10/11/aarp-made-billions-denying-care-people-pre-existing-conditions/.

[26] 2018 Consolidated Financial Statements, pp. 14-15.

[27] Ibid.

[28] 2017 Consolidated Financial Statements, pp. 4, 11.

[29] 2018 Consolidated Financial Statements, p. 14.

[30] 2010 through 2018 Consolidated Financial Statements.

[31] 2018 Consolidated Financial Statements, p. 19.

[32] Ibid.

[33] 2000 through 2018 Consolidated Financial Statements.

[34] 2008 Consolidated Financial Statements, p. 15; AARP Inc., 2015 Consolidated Financial Statements, March 17, 2016, https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/about_aarp/annual_reports/2016/2015-financial-statements-AARP.pdf, p. 14.

[35] 2000 through 2018 Consolidated Financial Statements. While AARP has previously disclosed that most of its royalty fees come from UnitedHealthGroup, AARP has never disclosed the precise percentage of grantor trust investment income attributable to policies sold by UnitedHealth.

[36] 2018 Form 990, p. 8.

[37] AARP Inc., 2006 Form 990, https://projects.propublica.org/nonprofits/display_990/951985500/2008_02_EO%2F95-1985500_990O_200612, pp. 1, 14.

[38] AARP Inc., 2014 Form 990, https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/about_aarp/annual_reports/2015-08/2014-IRS-Form-990-AARP.pdf, p. 10.

[39] 2018 Form 990, pp. 8-9.

[40] Ibid., pp. 1, 8.

[41] Ibid., pp. 1, 8.

[42] Social Security Administration, “Fact Sheet: 2018 Social Security Changes,” November 2017, https://www.ssa.gov/news/press/factsheets/colafacts2018.pdf.

[43] 2018 Form 990, pp. 1, 10.

[44] Markon, “AARP Lobbies Against Changes.”

[45] House Ways and Means Committee, “Behind the Veil: The AARP America Doesn’t Know,” March 30, 2011, https://gop-waysandmeans.house.gov/UploadedFiles/AARP_REPORT_FINAL_PDF_3_29_11.pdf, Table 2, p. 9.

[46] Ibid., pp. 11-12.

[47] Gary Cohn and Darrell Preston, “AARP’s Stealth Fees Often Sting Seniors with Costlier Insurance,” Bloomberg December 4, 2008, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2008-12-04/aarp-s-stealth-fees-often-sting-seniors-with-costlier-insurance.

[48] 2019 Fortune 500.

[49] Lee Hammond, AARP President, Letter to the Editor, Wall Street Journal January 11, 2011, https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052748704415104576065993584399626.

[50] McKinsey, “Exchanges Three Years In: Market Variations and Factors Affecting Performance,” May 2016, https://healthcare.mckinsey.com/exchanges-three-years-market-variations-and-factors-affecting-performance.

[51] Freudenheim, “AARP Dropping Plans.”

[52] Ibid.; Section 1128B of the Social Security Act, 42 U.S.C. 1320a-7b.

[53] Freudenheim, “AARP Dropping Plans.”

[54] UnitedHealthGroup, Inc, 2018 Form 10-K, February 12, 2019, https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/731766/000073176619000005/unh2018123110-k.htm, p. 28.

[55] For instance, online broker eHealthInsurance found an average Medigap premium of $141 per month in 2018 and $152 per month in 2019 among its customers; see eHealthInsurance, “Medicare Index Report: Annual Enrollment Period for 2019 Coverage,” February 7, 2019, https://news.ehealthinsurance.com/_ir/68/20191/eHealth%20Medicare%20AEP%20Report.pdf, p. 2. Business Insider used a survey by HealthView Services to cite an average premium of $143 per month for Medigap Plan F, the most popular Medigap plan, in 2018; see Hillary Hoffower, “Medicare Isn’t Enough for Retirees—Here’s How Much Extra Coverage Costs in Every State, Ranked,” Business Insider June 17, 2018, https://www.businessinsider.com/how-much-medigap-plans-cost-every-state-ranked-2018-6. Another brokerage site quoted an average premium of $169.14 for Medigap Plan F in 2018, the fourth highest among the 10 types of Medigap plans surveyed; see Christian Worstell, “What Is the Average Cost of Medicare Supplement Insurance Plan F?” October 3, 2019, https://www.medicaresupplement.com/articles/average-cost-of-medicare-supplement-plan-f/.

[56] The precise numbers in question would equal $8.181 billion and $404.96 million, respectively. However, because these numbers are based on rough approximations of premiums, we have provided ranges above.

[57] 2018 Consolidated Financial Statements, p. 4.

[58] Markon, “AARP Lobbies Against Changes.”

[59] While the congressional “supercommittee” could not reach agreement in 2011 on a package of entitlement reforms, Congress did eventually enact modest changes to Medigap insurance. Section 401 of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015, P.L. 114-10, provided that beginning in January 2020, Medigap policies sold to new Medicare beneficiaries (i.e., those just turning 65) cannot provide coverage for the Medicare Part B deductible, a measure designed to reduce unnecessary utilization of the health care system.

[60] Kaiser Family Foundation, “Medigap Reforms: Potential Effects of Benefit Restrictions on Medicare Spending and Beneficiary Costs,” July 2011, https://www.kff.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/8208.pdf, Exhibit 2: Changes in Medicare Spending Per Beneficiary and Average Beneficiary Costs under Three Medigap Benefit Options, p. 6.

[61] Markon, “AARP Lobbies Against Changes.”

[62] Ibid.

[63] Cohn and Preston, “AARP’s Stealth Fees.”

[64] Markon, “AARP Lobbies Against Changes.”

[65] Section 1882(s)(2) of the Social Security Act, 42 U.S.C. 1395ss(s)(2).

[66] Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2019 Report of the Boards of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Funds, April 22, 2019, https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/ReportsTrustFunds/Downloads/TR2019.pdf, p. 6.

[67] Shailagh Murray and Lori Montgomery, “Senate Health Care Bill Unlikely to Include Medicare Buy-In,” Washington Post December 15, 2009, https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/12/14/AR2009121401580.html?sid=ST2009121401946.

[68] Section 1234 of House Democrats’ Tri-Committee Discussion Draft, June 19, 2009, https://waysandmeans.house.gov/sites/democrats.waysandmeans.house.gov/files/media/pdf/111/HRdraft1xml.pdf.

[69] Susan Jaffe, “Medigap Supplemental Coverage Can Be Too Pricey for Younger Medicare Beneficiaries,” Kaiser Health News March 7, 2011, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2011/03/07/AR2011030703978.html.

[70] Congressional Budget Office, Preliminary Estimate of the House Tri-Committee Discussion Draft, July 8, 2009, https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/111th-congress-2009-2010/costestimate/preliminaryestimatedivisionb0.pdf, p. 5.

[71] Letter from AARP Chief Operating Officer Thomas Nelson to Rep. Dave Reichert, November 2, 2009, p. 4.

[72] AARP Inc., 2011 Consolidated Financial Statements, March 23, 2012, https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/about_aarp/annual_reports/2012-05/Consolidated-Financial-Statements-2011-2010-AARP.pdf, pp. 4, 9; AARP Inc., 2009 Consolidated Financial Statements, March 24, 2010, https://assets.aarp.org/www.aarp.org_/cs/misc/2009_aarp_consolidated_financial_statements_12_31_09.pdf, pp. 3, 9.

[73] Hammond, Letter to the Editor; Karl Rove, “ObamaCare Rewards Friends, Punishes Enemies,” Wall Street Journal January 6, 2011, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704405704576063892468779556.html.

[74] Jaffe, “Medigap Supplemental Coverage.”

[75] Section 9010(h)(3)(C) of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA), P.L. 111-148.

[76] PPACA Section 9010(e).

[77] 2017 Consolidated Financial Statements, pp. 5, 11.

[78] Section 502 of Division N of the Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020, P.L. 116-94.

[79] Section 2718(b) of the Public Health Service Act, 42 U.S.C. 300gg-18(b), as codified by PPACA Section 1001(5).

[80] Section 1882(r)(1) of the Social Security Act, 42 U.S.C. 1395ss(r)(1).

[81] Department of Health and Human Services, Rate Increase Disclosure and Review, Final Rule, Federal Register May 23, 2011, http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2011-05-23/pdf/2011-12631.pdf, pp. 29966-67, 29985.

[82] Department of Health and Human Services, Rate Increase Disclosure and Review, Proposed Rule, Federal Register 23 December 2010, http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2010-12-23/pdf/2010-32143.pdf, pp. 81007, 81009, 81026.

[83] Chris Jacobs, “A Reading Guide to the Senate Bill’s Backroom Deals,” March 2, 2010, https://chrisjacobshc.com/2010/03/02/a-reading-guide-to-the-senate-bills-backroom-deals-2/

[84] Dan Eggen, “AARP: Reform Advocate and Insurance Salesman,” Washington Post October 27, 2009, https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/10/26/AR2009102603392_pf.html.