Why Smaller Premium Increases May Hurt Republicans in November

Away from last week’s three-ring circus on Capitol Hill, an important point of news got lost. In a speech on Thursday in Nashville, Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) Alex Azar announced that benchmark premiums—that is, the plan premium that determines subsidy amounts for individuals who qualify for income-based premium assistance—in the 39 states using the federal healthcare.gov insurance platform will fall by an average of 2 percent next year.

That echoes outside entities that have reviewed rate filings for 2019. A few weeks ago, consultants at Avalere Health released an updated premium analysis, which projected a modest premium increase of 3.1 percent on average—a fraction of the 15 percent increase Avalere projected back in June. Moreover, consistent with the HHS announcement on Thursday, Avalere estimates that average premiums will actually decline in 12 states.

On the other hand, however, given that Democrats have attempted to make Obamacare’s pre-existing condition provisions a focal point of their campaign, premium increases in the fall would remind voters that those supposed “protections” come with a very real cost.

How Much Did Premiums Rise?

The Heritage Foundation earlier this year concluded that the pre-existing condition provisions collectively accounted for the largest share of premium increases due to Obamacare. But how much have these “protections” raised insurance rates?

Overall premium trend data are readily available, but subject to some interpretation. An HHS analysis published last year found that in 2013—the year before Obamacare’s major provisions took effect—premiums in the 39 states using healthcare.gov averaged $232 per month, based on insurers’ filings. In 2018, the average policy purchased in those same 39 states cost $597.20 per month—an increase of $365 per month, or $4,380 per year.

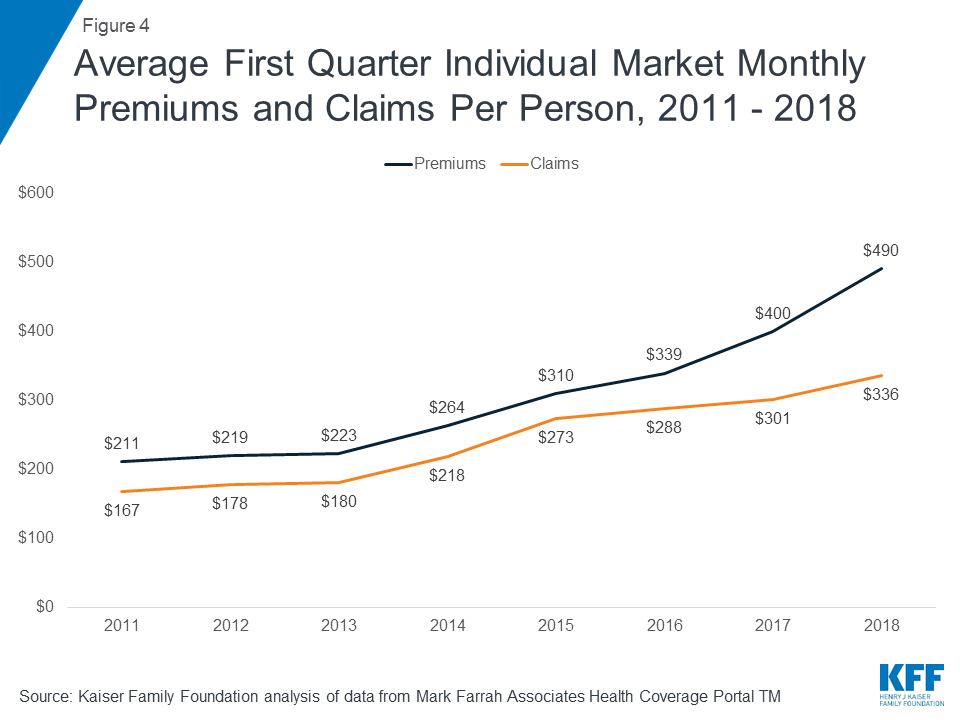

Moreover, the trends hold for the individual market as a whole—which includes both exchange enrollees, most of whom qualify for subsidies, and off-exchange enrollees, who by definition cannot. The Kaiser Family Foundation estimated that, from 2013 to 2018, average premiums on the individual market rose from $223 to $490—an increase of $267 per month, or $3,204 per year.

Impact of Pre-Existing Condition Provisions

The HHS data suggest that premiums have risen by $4,380 since Obamacare took effect; the Kaiser data, slightly less, but still a significant amount ($3,204). But how much of those increases come directly from the pre-existing condition provisions, as opposed to general increases in medical inflation, or other Obamacare requirements?

The varying methods used in the actuarial studies make it difficult to compare them in ways that easily lead to a single answer. Moreover, insurance markets vary from state to state, adding to the complexity of analyses.

However, given the available data on both how much premiums rose and why they did, it seems safe to say that the pre-existing condition provisions have raised premiums by several hundreds of dollars—and that, taking into account changes in the risk pool (i.e., disproportionately sicker individuals signing up for coverage), the impact reaches into the thousands of dollars in at least some markets.

Republicans’ Political Dilemma

Those premium increases due to the pre-existing condition provisions are baked into the proverbial premium cake, which presents the Republicans with their political problem. Democrats are focusing on the impending threat—sparked by several states’ anti-Obamacare lawsuit—of Republicans “taking away” the law’s pre-existing condition “protections.” Conservatives can counter, with total justification based on the evidence, that the pre-existing condition provisions have raised premiums substantially, but those premium increases already happened.

If those premium increases that took place in the fall of 2016 and 2017 had instead occurred this fall, Republicans would have two additional political arguments heading into the midterm elections. First, they could have made the proactive argument that another round of premium increases demonstrates the need to elect more Republicans to “repeal-and-replace” Obamacare. Second, they could have more easily rebutted Democratic arguments on pre-existing conditions, pointing out that those “popular” provisions have sparked rapid rate increases, and that another approach might prove more effective.

Instead, because premiums for 2019 will remain flat, or even decline slightly in some states, Republicans face a more nuanced, and arguably less effective, political message. Azar actually claimed that President Trump “has proven better at managing [Obamacare] than the President who wrote the law.”

Conservatives would argue that the federal government cannot (micro)manage insurance markets effectively, and should not even try. Yet Azar tried to make that argument in his speech Thursday, even as he conceded that “the individual market for insurance is still broken.”

‘Popular’ Provisions Are Very Costly

The first round of premium spikes, which hit right before the 2016 election, couldn’t have come at a better time for Republicans. Coupled with Bill Clinton’s comments at that time calling Obamacare the “craziest thing in the world,” it put a renewed focus on the health-care law’s flaws, in a way that arguably helped propel Donald Trump and Republicans to victory.

This year, as paradoxical as it first sounds, flat premiums may represent bad news for Republicans. While liberals do not want to admit it publicly, polling evidence suggests that support for the pre-existing condition provisions plummets when individuals connect those provisions to premium increases.

The lack of a looming premium spike could also neutralize Republican opposition to Obamacare, while failing to provide a way that could more readily neutralize Democrats’ attacks on pre-existing conditions. Maybe the absence of bad news on the premium front may present its own bad political news for Republicans in November.

This post was originally published at The Federalist.